One day during the Iraqi war, I started thinking about the old idea "make love, not war". Could it be true that if our leaders spent more time making love, they would make less war? The media certainly has an easier time displaying violence and violent sex, rather than affection and loving sex.

Peter Good, author of The Monkey Experiment, called my attention to the cross-cultural studies of James Prescott -- which indicate that physical affection during infancy and adolescence reduces violence. So, "make love, not war" may even have a scientific basis.

We have yet to learn how to be for life rather than against life. Perhaps our leaders would do well to learn how to "make love, not war" and thereby set an example for a peaceful society. The following passage from Prescott is suggestive of a new way of looking at war and peace:

"The strength of the two-stage deprivation theory of violence is most vividly illustrated when we contrast the societies showing high rates of physical affection during infancy and adolescence against those societies which are consistently low in physical affection for both developmental periods. The statistics associated with this relationship are extraordinary: The percent likelihood of a society being physically violent if it is physically affectionate toward its infants and tolerant of premarital sexual behavior is 2 percent (48/49). The probability of this relationship occurring by chance is 125,000 to one. I am not aware of any other developmental variable that has such a high degree of predictive validity. Thus, we seem to have a firmly based principle: Physically affectionate human societies are highly unlikely to be physically violent."

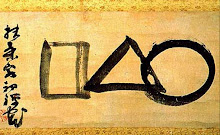

Image from McMaster University - U. S. Sixties History.